Here is another guest spot from Vernon Benjamin. Not exactly about Gotham, but at less than twenty miles away, Dobbs Ferry is in the city’s orbit. (Heck, so is everything south of Albany, I figure.) And besides, the renaming of streets and institutions in the wake of the Revolutionary War was a commonplace in New York City–King’s College becoming Columbia; Queen Street becoming Pearl Street; Duke Street becoming Stone Street; and so on. (Indeed, the very next post in this space will be a list of all the old street names, going back to Dutch times, and what later became of them.) This year Mr. Benjamin published a work two decades in the making, the indispensable The History of the Hudson River Valley: From Wilderness to the Civil War. The story below will appear in that book’s sequel, The History of the Hudson River Valley: 1865-2015, forthcoming from Overlook Press.

Here is another guest spot from Vernon Benjamin. Not exactly about Gotham, but at less than twenty miles away, Dobbs Ferry is in the city’s orbit. (Heck, so is everything south of Albany, I figure.) And besides, the renaming of streets and institutions in the wake of the Revolutionary War was a commonplace in New York City–King’s College becoming Columbia; Queen Street becoming Pearl Street; Duke Street becoming Stone Street; and so on. (Indeed, the very next post in this space will be a list of all the old street names, going back to Dutch times, and what later became of them.) This year Mr. Benjamin published a work two decades in the making, the indispensable The History of the Hudson River Valley: From Wilderness to the Civil War. The story below will appear in that book’s sequel, The History of the Hudson River Valley: 1865-2015, forthcoming from Overlook Press.

Dobbs Ferry lost its name for forty years after 1830. Van Brugh Livingston (1792-1868), who had a mansion on the river, filed deeds naming the dockside “Livingston’s Landing,” to the great dissatisfaction of the locals. Westchester already had too many identity changes with the incredible period of growth that was occurring in the birthing of America, and was exploding in uncomfortable ways in the industrial and urban expansion of the times. True, a similar proliferation of country seats, recreational resources, and waterfront accessories along the Hudson and Long Island Sound ameliorated some of these distasteful changes, but where would it stop?

New York City’s need for the county’s rich water resources was preventing significant growth in the central and northeastern areas of the county, a mixed blessing for all but the city. Livingston’s new dockside was part of the commercial growth, and the change in identity brought with it new frustrations for the locals to endure. Some of the river towns, to be sure, were benefiting from their identification with the Ichabod Crane land of Washington Irving, but now this. Would the whole of the American Revolution be thrown out with the names?

The dugout canoe ferry that Jeremiah Dobbs began using at Willow Point in the eighteenth century had continued in successively reinvented forms until, by 1915, a light motorboat came into use. The boat was summoned by a wooden signal with a rope that, when pulled, displayed a black square on white wood clearly visible from across the river. So why change the name of the place so long associated with this ferry? The notion annoyed the old-timers like a bad tooth, even though there were uncomfortable associations with the original name. Dobbs was a Loyalist on the British side during the Revolution.

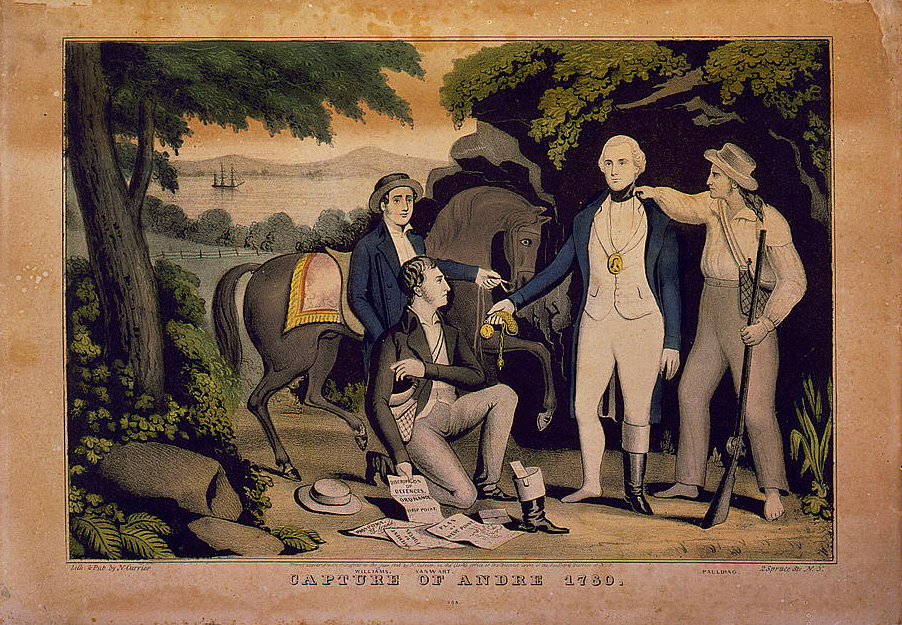

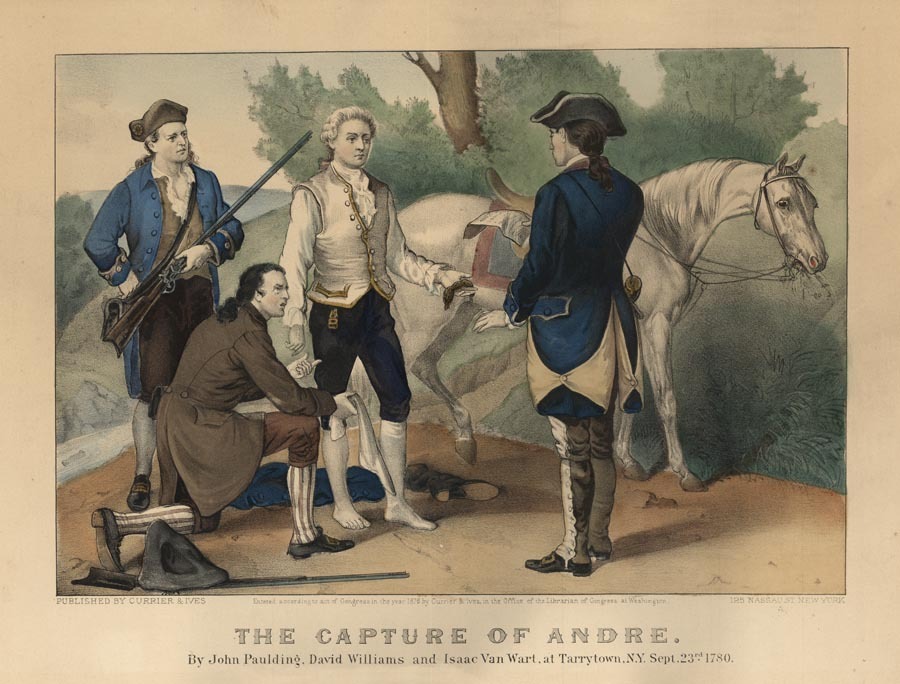

After Livingston’s death, in 1870 a meeting was convened to come up with a better choice of names for this historic place. Resuming the old Dobbs Ferry name was frowned upon because of Dobbs’ association with the British. Yet the fame of the town, as with the region, had grown as a result of the Benedict Arnold scandal over the treason of West Point and the capture of his British co-conspirator, John André (1750-80). André’s ship, the Vulture, retreated to the waters off Dobbs Ferry after being chased off from Verplanck’s Point by patriots with cannon, a distance too great for André to have traversed by rowboat from Haverstraw Bay, where he had met with Arnold; he had to take an overland route, and that let to his capture. In contrast to the taint of loyalism in the ferryman’s family, the obvious choice for the new Dobbs Ferry seemed to be the patriotic one.

But which one? Three men out on patrol on militia duty—or, as André and the American colonel Benjamin Talmadge (1754-1835) claimed, brigands looking for some booty to steal—had captured the British spy. The crowd discussed the idea of renaming the location “Paulding-on-Hudson” in honor of one of the captors, but an old man rose and made a speech against it, perhaps remembering that John Paulding (1758-1818) was born in Peekskill. He said he had known Paulding personally “and could not brook him.” No one was interested in another Williamstown—after David Williams (1754-1831), another of the captors—so the man suggested that the third member of the threesome that caught André might make a good choice. He was Isaac Van Wart (1762-1828), and if the Van were dropped, the old fellow suggested, the town could comfortably be called “Wart-on-Hudson.”

The amusement that the suggestion provoked may have been tempered by the changing nature of the county itself, but it also showed that the community could appreciate the humor in a historic name. The meeting, and the idea, broke up in guffaws. The town dropped the Livingston manorial name and resumed using the old moniker of the Tory ferryman. Bygones were going to be bygones after all.