Every street name has a story. Let me tell you one, which may be my favorite–about Raisin Street–and maybe also another, regarding the original Murderers’ Row–no, it did not start with the 1927 Yankees. This will be a longish post, even after breaking it out into two segments, so as not make street search utterly maddening. Of course many streets have been renamed, usually in tandem with a prior name (52nd Street, or rather a portion of it, a.k.a. “Swing Street”) .

Every street name has a story. Let me tell you one, which may be my favorite–about Raisin Street–and maybe also another, regarding the original Murderers’ Row–no, it did not start with the 1927 Yankees. This will be a longish post, even after breaking it out into two segments, so as not make street search utterly maddening. Of course many streets have been renamed, usually in tandem with a prior name (52nd Street, or rather a portion of it, a.k.a. “Swing Street”) .

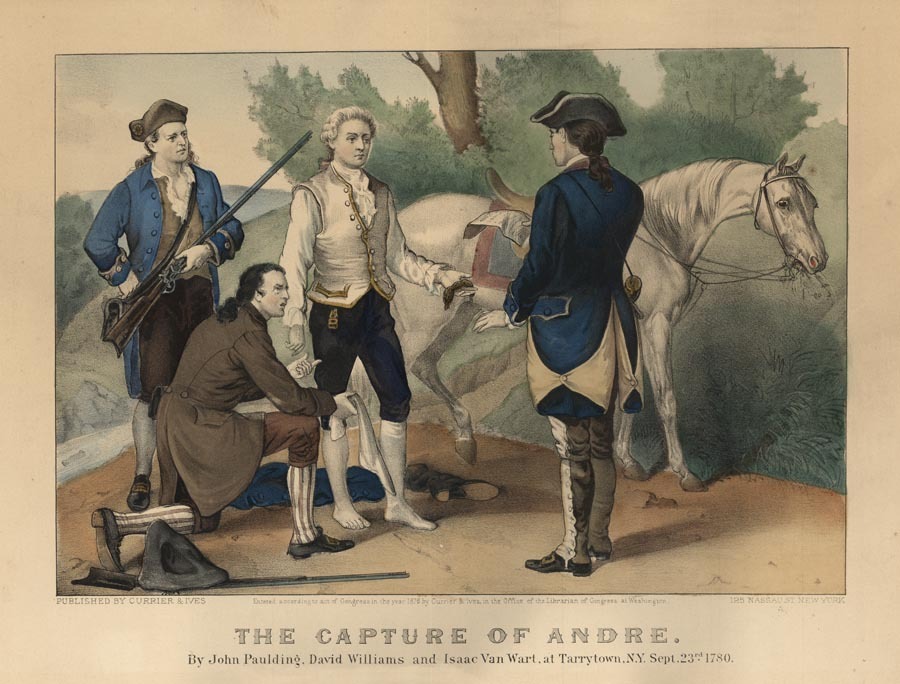

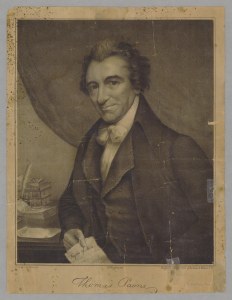

Thomas Paine, lith. by Bufford ca. 1838

First, Raisin Street: Originally dubbed Reason Street, after Thomas Paine’s The Age of Reason; between Bleecker and Bedford Sts.; name changed in 1828. New York’s accent is said to have transformed Reason Street into Raison Street–over time altered further and even written as Raisin Street. It seems to me, though, that both names must have coexisted, as Paine left America for France to aid in the French Revolution, and raison is the French word for reason. Trinity Church, which owned land along the street, was unhappy about this commemoration of the free-thinking “atheistic” Paine–who certainly recognized a Supreme Being–and got the street renamed for Thomas Barrow, an artist whose 1776 drawing of Trinity’s great fire was very popular. Below is an 1861 lithograph by George Hayward, based on Barrow’s drawing made on the spot.

Barrow, Ruins of Trinity Church, 1776

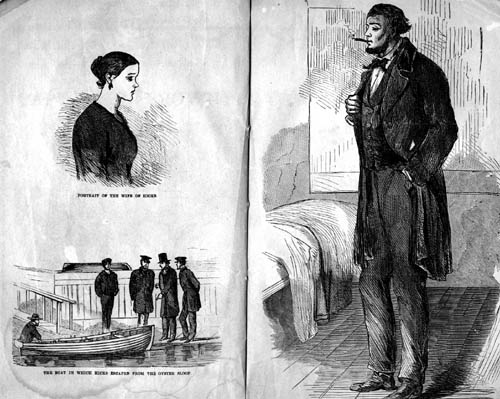

Second, Murderers’ Row: The usual etymology for this term is plausible–that it derives from a row of cells in New York’s Tombs reserved for the most dastardly of criminals. This passage from Meyer Berger’s The Eight Million: Journal of a New York Correspondent (Columbia University Press, 1983), while not a contemporary description, does testify to a separate domicile for murderers.

There were four tiers of cells. Convicted prisoners had the ground floor and those awaiting trial had the other three; murderers occupied the second, burglars and arsonists the third, and minor offenders the fourth. Homeless children seven and eight years old were thrown into cells with prostitutes, alcoholics, and cutpurses.

Yet this fact gleaned from Charles A. Hemstreet’s Nooks and Crannies of Old New York (Scribner, 1899) may give pause: Murderers’ Row was an actual alley long before the Civil War, starting where Watts Street ended at Sullivan Street, midway along the block between Grand and Broome Streets. Now part of the fashionable Soho district, Murderers’ Row was one of many mean streets in the neighborhood later known as Darktown–as the Chinese had Chinatown and the Jews had Jewtown (yes, that was what they called the Lower East Side in the years before 1900; and there was a “Jew’s Alley,” which ran from Madison St. between Oliver and James Streets).

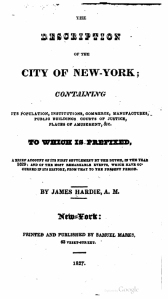

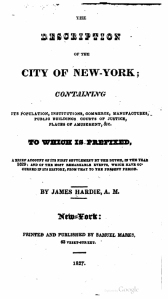

The alley that Hemstreet called “Murderers’ Row” existed in 1827 and was called “Otter’s-alley” in James Hardie’s Description of the City of New York, which was printed and published in that year by Samuel Marks, 63 Vesey Street. From this book I was also able to confirm that all the streets mentioned in Hemstreet had indeed been cut through: Sullivan, Watts, Grand, and Broome. The alley/row ran east-west, connecting Sullivan and Thompson Streets.

The sticking point: precisely when someone called this thoroughfare Murderers’ Row, in print, for the first time. Let me quote from Paul Dickson’s estimable Dictionary of Baseball Quotations (Facts on File, 1989):

ETY/1ST 1858. According to Bill Bryson in his April 1948 Baseball Digest article entitled ‘Why We Say It,’ the writer who first called the Ruth-Gehrig-Meusel-Lazzeri combo Murderers’ Row, ‘… probably drew praise from his boss for a “fresh, vibrant phrase.” He then points out, ‘Well, it had been used in a New York newspaper’s account of a game a few years before that–about seventy years in fact. The 1858 writer got it from the name given the isolated rows of cells containing dangerous criminals in the Tombs prison in New York.’ Edward J. Nichols concurs, pointing out in his dissertation that there is a clipping in Henry Chadwick’s Scrapbook from 1858 in which it was applied to a lineup of power hitters.

Hardie, 1827

Boy, I’d love to see that clip, as Chadwick abhorred the slugging style of play and is himself unlikely to have coined the term Murderers’ Row as a colorful approbation. Moreover, the Tombs opened for business in 1838 and the alley almost surely predates that year. My belief is that the Tombs sense of the phrase Murderers’ Row cannot be earlier than 1840, and that the alley-way provides an earlier usage.

Checking an 1827 listing of street names, I found that Hemstreet’s location matched a street name: Otter’s Alley. As you will see in an entry below, “Otter’s Alley formerly ran from Thompson to Sullivan Sts. between Broome and Grand Sts.”–very nearly the same wording as in Hemstreet.

Enough preamble; on with the show, from Valentine’s Manual of Old New York, 1923; No. 7, New Series; edited by Henry Collins Brown.

STREET NAMES WHICH HAVE BEEN CHANGED OR ARE NOW OBSOLETE IN THE BOROUGH OF MANHATTAN, NEW YORK CITY—1922.

By George Henry Stegmann

The following information regarding Old New York Streets was obtained from the following sources:

VALENTINE’S MANUAL — 1855; 1860; 1861; 1862; 1864; 1865; 1866.

Haswell — Reminiscences of an Octogenarian.

Hill — Story of a Street (Wall Street).

Historical Guide to the City of New York — .

Innes — New Amsterdam and its People.

Jenkins — The Greatest Street in the World.

Jenkins — The Old Boston Post Road.

Lossing — History of New York City.

Lamb — History of New York City.

Mott — New York City of Yesterday.

Pasko — New York Old and New.

Post — Old Streets, Roads, Lanes, etc., of New York.

Riker — History of Harlem.

Valentine — History of New York City.

Wilson — New York Old and New.

Plan of the City of New York—

1665, Duke’s Plan.

1695. Duke’s Plan.

1728, Jas. Lyne.

1742, D. Grim.

1764, S. Bellini.

1755, F. Maerschaick.

1766, B. Ratzer.

1775, John Montressor.

1797.

1803, Goerck & Mangin.

1807, Wm. Bridges.

1817, T. H. Poppelton.

1851.

1865.

1868.

Bromley’s Atlas of the Borough of Manhattan.

[Many street names have been entirely discontinued. Old Love Lane, formerly Twenty-first Street west of Fifth Avenue, is a case in point. And this list might easily be lengthened. We ought to celebrate great Americans when new names are needed, and get away from the tiresome numerical system heretofore slavishly followed.]

Abingdon Place was the former name of West 12th St. between Hudson and Greenwich Sts. It was laid out about 1807; known then as Cornelia St.; in 1817 known as Scott St.

Abingdon Road, see Love Lane.

Abattoir Place was the former name of West 12th St. between 11th Ave. and the Hudson River.

Achmuty Lane was in block bounded by Water, South, Pike and Rutgers Sts.

Adams Place was the former name of West Broadway between Spring and Prince Sts.

Albany Avenue formerly ran from 26th St. between 5th and Madison Ave. northwesterly, crossing 5th Ave. between 29th and 30th St. to the corner of 6th Ave. and 42nd St., then northerly on the present line of 6th Ave. to 93rd St.

Albion Place was the former name of East 4th St. between 2nd Ave. and the Bowery.

Amity Alley (or Amity Place) was formerly in the rear of No. 216 Wooster St.

Amity Lane was a country lane which commenced at Broadway, about fifty feet north of Bleecker St. and ran northwesterly to 6th Ave. just south of 4th St.

Amity Street was the former name of West 3rd St. between Broadway and 6th Ave.

Amos Street was the former name of West 10th St. between Greenwich Ave. and the Hudson River.

Ann Street was the former name of Grand St. between Broadway and the Bowery. It was laid out in 1797 and its name was changed to Grand St. in 1807.

Ann Street was [also] the former name of Elm St. between Reade and Franklin Sts. Name was changed in 1807.

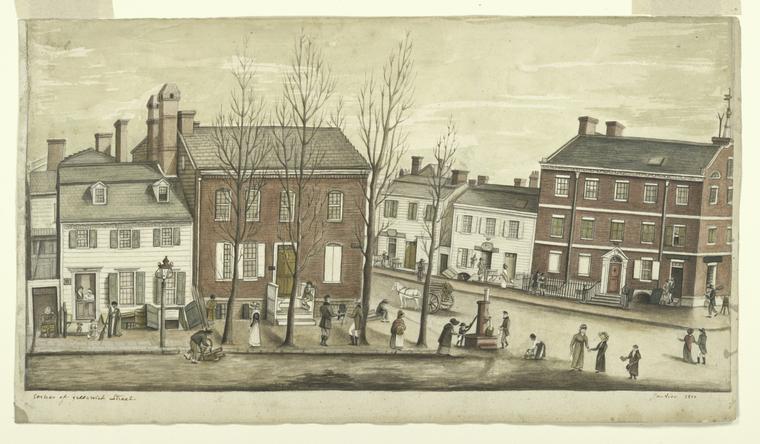

View of a Section of Ann and Nassau Streets, from Around the Corner, Anderson and Davis, Mirror, Sept 4, 1830

Anthony Street, Duane St. was called by this name at one time.

Anthony Street was the former name of Worth St. between Hudson and Baxter Sts. It was laid out in 1795; known in 1797 as Catherine St.; known in 1807 as Anthony St.

Arch Place was in the rear of No. 109 Canal St., between Church St. and West Broadway.

Arden Street was the former name of Morton St. between Varick and Bleecker St.; name was changed in 1829. It was also called Eden St.

Arundel Street was the former name of Clinton St. from Division to Houston Sts. It was laid out about 1760; name changed to Clinton St. in 1828.

Art Street was the former name of Astor Place. Originally it was a lane leading from the Bowery to a part of the Stuyvesant Farm. It was known as Art St. in 1807.

Ashland Place was the former name of Perry St. between Waverly Place and Greenwich Ave.

Asylum Street was the former name of West 4th St., between 6th Ave. and 13th St.

Augustus Street was the former name of City Hall Place. It was laid out about 1795; known as Augustus St. in 1797.

Bache Street, Beach St. was called by this name at one time.

Bailey Street was laid out through the New York Common Lands, it ran from Broadway to Albany Ave. between 25th and 26th Sts.

Bancker Street, Duane St. was at one time called by this name.

Bancker Street was the former name of Madison St. between Catherine and Pearl Sts. It was projected about 1750; known as Bancker St. in 1755; known as Madison St. since.

Bannon Street was the former name of Spring St.

Bar Street as laid out, ran from Grand St. to the East River between Scammel and Jackson Sts. It was also called Fir St.

Barley Street was the former name of Duane St. from Rose to Hudson Sts. It was laid out in 1791; name changed to Duane St. in 1807.

Barrack Street was the former name of Tyron Row (now obsolete); known by this name in 1766.

Barrick Street; Exchange Place was known by this name at one time.

Barrow Street; West Washington Place, between Macdougal and West 4th St., was known by this name at one time.

Batavia Lane was name of Batavia Street.

Battoe Street; Dey St. was so called at one time.

Bayard Place, now called Charles Lane; a narrow street running from Washington West St. between Charles and Perry Sts.

Bayard Street, Stone St. was so called at one time, Beaver Lane was the first name of Morris St.

Bedlow Street was the former name of Madison St. between Catherine and Montgomery Sts. It was known by this name in 1797; known as Bancker St. in 1817.

Belvedere Place was the former name of West 10th St.

Benson’s Lane was the former name of Elm St.

Bever Graft, Bever Straat, Bever Paatjie, were the Dutch names of Beaver St. from Broadway to Broad St.

Beurs Straat was the Dutch name of Whitehall St.

Bloomfield Street formerly ran from No. 7 10th Ave. to the Hudson River (now closed).

Clendening Mansion at Bloomingdale Road, Valentine’s Manual, 1863

Bloomingdale Road started at 23rd St., being the continuation of Broadway at that point. It followed the present Broadway as far as 86th St., where it veered easterly, running between Broadway and Amsterdam Ave. At 104th St. it again followed the line of Broadway until reaching 107th St., where it turned slightly westerly until it met the present easterly roadway of Riverside Drive, following it to 116th St., where it turned easterly, crossing Broadway at 126th St. and meeting Old Broadway at Manhattan St. (the present Old Broadway between Manhattan St. and 133rd St. is a part of the original road). From 133rd St. it ran slightly east of the present Broadway into Hamilton Place at 138th St., following Hamilton Pl. to its termination at Amsterdam Ave. and 144th St., from there running northeasterly and ending at the junction of Kingsbridge Road, just east of St. Nicholas Ave. and 147th St.

Bogart Street formerly ran from No. 539 West St. west to the Hudson River.

Boorman Terrace, West 32nd St. between 8th and 9th Ave.

Boston Post Road, see Eastern Post Road.

Bott Street was the former name of Elm St.

Boulevard, The, was the former name of Broadway from 59th to 155th St., it was opened in 1868 and name changed to Broadway on Jan. 1, 1899.

Boulevard Place was the former name of West 130th St. from 5th to Lenox Ave.

Bowery Lane. The Bowery was called by this name in 1760; since 1807 known as the Bowery.

Bowery Place was in the rear of No. 49 Christie St., between Canal and Hester Sts.

Bowling Green, Cherry St. was called by this name at one time.

Breedweg, Breedwegh. Broadway between Bowling Green and Park Row was known by these names during the Dutch occupancy of the City.

Brevoort Place was the former name of West 10th St. between Broadway and University Place.

Brewers Hill was the former name of Gold St.

Bride Street was the former name of Minetta St. from Bleecker St. to the bend in the street.

Bridge Street was one of the former names of Elm St.

Broad Wagon Way, The, was the name of Broadway in 1670.

Broadway Alley formerly ran from No. 153 East 26th St. north to 27th St.

Brook Street was the former name of Hancock St.

![The Island of Manhados (with inset plan of) The Towne of New-York [The Nicolls Map or Survey], 1664-8.](https://gothamhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/plate-10-a-a-the-island-of-manhados-with-inset-plan-of-the-towne-of-new-york-the-nicolls-map-or-survey-1664-8.png?w=1000&h=347)

The Island of Manhados (with inset plan of) The Towne of New-York [The Nicolls Map or Survey], 1664-8.

(Brewer’s St.) was the name of the Dutch first gave to the present Stone St. It was one of the earliest streets laid out by them and received this name on account of the Brewery of the West India Co. being located on it. Since 1797 has been known as Stone St., having been called High St. in 1674, and Duke St. in 1691.

Brugh Straet (Bridge Street) was one of the early Dutch Streets and received this name on account of it being the street which led to the bridge over the Canal in Broad St.; known as Bridge St. in 1674; as Hull St. in 1691; and as Bridge St. since 1728.

Brugh Steegh (Bridge Lane) was a narrow street, about twenty-two feet wide, which ran between Bridge and Stone Sts. It was closed about 1674.

Budd Street was the former name of Van Dam St.

Bullock Street was the former name of Broome St.; known by this name in 1766; since 1807 known as Broome St.

Burgers Path was the Dutch name of a part of William St.

Burling Lane was a country road which commenced at the present Broadway, between 17th and 18th Sts., and ran southwesterly, meeting the Southampton Road at about the present 6th Ave. and 16th St.

Burnet Street was the former name of Water St. between Wall St. and Maiden Lane.

Burr Street was the former name of Charlton St.

Burrows Street was the former name of Grove St. In 1807 was known as Columbia St. and since 1817 as Burrows St.

Burton Street was the former name of LeRoy St. from Varrick to Bleecker Sts.

Bushwick Street was the former name of Tompkins St.

Camden Place was the former name of East 11th St. between Avenue B and C.

Caroline Street was at the head of Duane St. Slip.

Carroll Place was the former name of Bleecker St. between West Broadway and Thompson St.

Cartmans Arcade was an Alley which ran south at No. 171 Delancey St., now closed.

Catherine Place was the former name of Catherine Lane.

Catherine Street was the former name of Worth St.; known in 1797 as Catherine St.; in 1807 as Anthony St.

Catherine Street was the former name of Waverly Pl. between Christopher and West 12th St.; known by this name in 1807.

Catherine Street was the former name of Mulberry St. between Bayard and Bleecker St.; known by this name in 1797.

Catherine Street was the former name of Pearl St. between Broadway and Elm St.; was also called Magazine St.

Cato’s Lane started at the Eastern Post Road, about the present 2nd Ave. between 52nd and 53rd St., and ran southeasterly to the East River at Ave. A between 50th and 51st Sts.

Chapel Street was the former name of West Broadway from Murray to Canal St.; known by this name in 1797; name changed to College Place in 1830. Chappel Street was the former name of Beekman St. Charles Chappel Street was the former name of Beekman St.

Charles Alley was the former name of Charles Lane.

Charlotte Street was the former name of Pike St. between Cherry and Division Sts.; was known by this name in 1791.

Pearl and Chatham, Valentine’s Manual, 1861

Chatham Street was the former name of Park Row. This street was originally part of the Bowery; called Chatham St. in 1774, changed to Park Row in 1886.

Cheapside was the former name of Hamilton St. between Catherine and Market Sts.; was known by this name in 1797; name changed to Hamilton St. on Aug. 27, 1827.

Chestnut Street was the former name of Howard St. between Broadway and Mercer Sts.; known in 1807 as Hester St.

Chester Street was the former name of West 4th St. between Bank and Christopher Sts.

Chrystie Street was the former name of Cherry St.

Church Lane was one of the first streets laid out in the village of Harlem, it ran from 117th St. between 3rd and 4th Aves, northerly to 120th St., then northeasterly, crossing 3rd Ave. at 121st St., 2nd Ave. at 123rd St. and ending at the Harlem River between 125th and 126th Sts.

Church Street was the former name of Exchange Place between Broadway and William St.

Clendenning’s Lane was a country road which started in Central Park about on line with 6th Ave. and 105th St. and ran westerly along the southerly side of 105th St. to the middle of the block between Columbus and Amsterdam Ave., then southwesterly to the Bloomingdale Road, at about a point fifty feet south of 103rd St.

Clermont Street was the former name of Mercer St.; known in 1797 as First St. and since 1807 as Mercer St.

Clermont Street was the former name of Hester St. between Center St. and Broadway and of Howard St. between Broadway and Mercer St.

Clinton Place was the former name of West 8th St., from Broadway to 6th Ave.

Colden Street was the former name of Duane St., from Lafayette to Rose St.; known by this name in 1803.

College Place was the former name of West Broadway from Barclay to Warren Sts.; known in 1755 as Chapel St.; name changed to College Pl. in 1830.

Collet Street was the former name of Center St. from Hester to Pearl Sts.; known by this name in 1807 to 1817.

Columbia Place was the former name of a part of 8th St.

Columbia Street was the former name of Grove St.; was also called Burrows and Cozine Sts.

Columbia Street was the former name of Jersey St.

Commerce Street was the former name of Barrow St.

Commons Street. Park Row was so called at one time.

Concord Street was the former name of West Broadway from Canal to 4th Sts.

Congress Place was the former name of an Alley in the rear of No. 4 Congress St.

Coopers Street was the former name of Fletcher St.

Cop Street was the former name of State St.

Cornelia Street was the former name of West 12th St. between Greenwich Ave. and Hudson St.

Cottage Place was the former name of East 3rd St. between Avenue B and C.

Cottage Row was the former name of 4th Ave. between 18th and 19th Sts.

Crabapple Street was the former name of Pike St.

Cropsie Street was the former name of State St.

Cozine Street was the former name of Grove St.

Cross Street was the former name of Park St.

Crown Point Street was the former name of Grand St. from the Bowery to the East River.

Crown Point Street was the former name of Corlears St.

Crown Point Street was the former name of Water St. between Montgomery St. and the East River.

Crown Street was the former name of Park St.; known in 1797 as Cross St.

Crown Street was the former name of Liberty St.; it was laid out about 1690; at one time called Tienhoven St.; name changed to Liberty St. in 1783.

Custom House St. was the former name of Pearl St., between Whitehall St. and Hanover Square.

David Street was the former name of Bleecker St., between Broadway and Hancock St.; name changed in 1829.

David Street was the former name of Clarkson St. between Varick and Hudson Sts.

Decatur Place was the former name of 7th St. between 1st Ave. and Avenue A.

Depau Row was the former name of Bleecker St. between Thompson and Sullivan Sts.

Desbrosses Street was the former name of Grand St. between Broadway and Varick St.

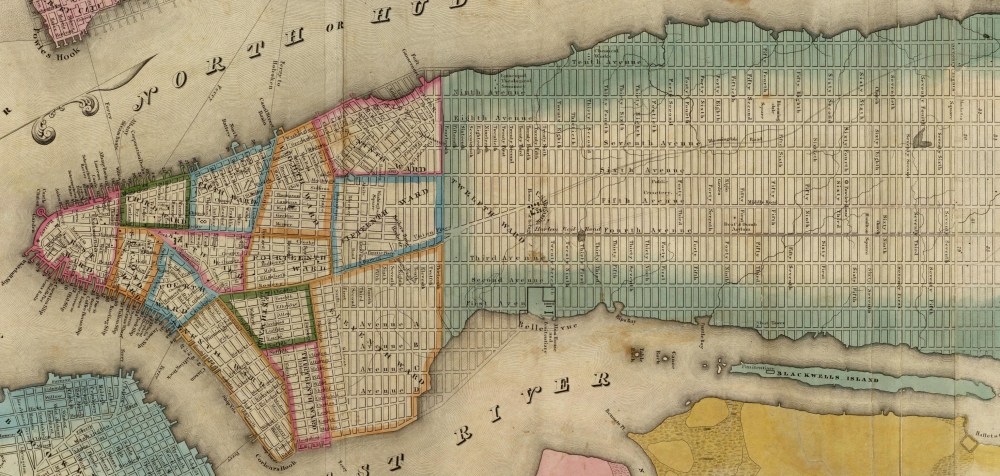

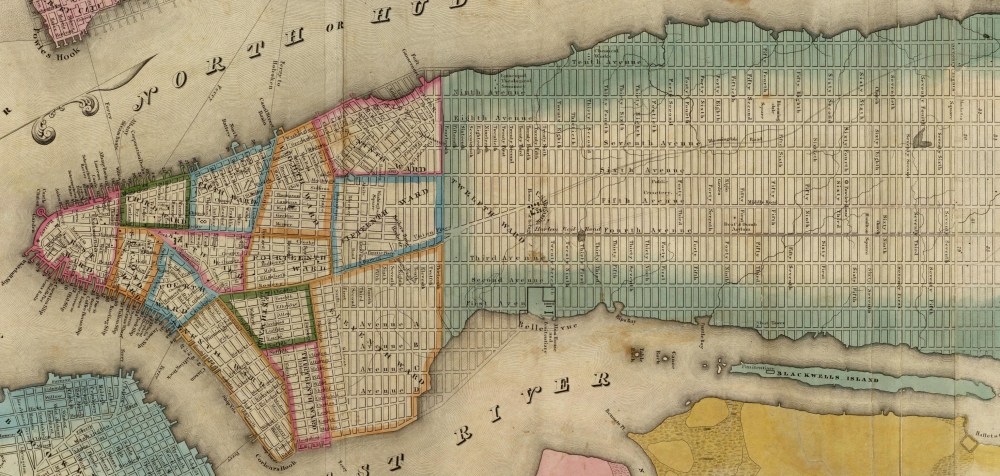

Extract from David Burr Atlas, NYC Ward Map, 1832.

Dirty Lane was the former name of South William St. This street was opened about 1656 and was called by the Dutch Slyck Steegh, meaning Dirty Lane. In 1674 it was called Mill Street Lane; name changed to South William St. about 1832.

Division Street was the former name of Fulton St. between Broadway and West St.

Dixson’s Row was the name given to a part of 110th St. between 8th and Columbus Ave.

Dock Street was the former name of Pearl St. between Whitehall St. and Hanover Square.

Dock Street was the former name of Water St. between Coenties Slip and Beekman St.

Dommic Street was the former name of Dowling St.

Donovan’s Lane was near No. 474 Pearl St.

Duggan Street was the former name of Canal St. between Center and West Sts.

Duke Street was the former name of Stone St. During the Dutch times a part was known as Brouwers Straet, and another part as Hoogh Straet; in 1674 was known as High St. and a part as Stone St. In 1691 it was called Duke St. and since 1797 has been known as Stone St. This street was the first to be paved with stone in the City.

Duke Street was the former name of Vanderwater St.; it was known by this name in 1755.

Duncomb Place was the former name of East 128th St. between 2nd and 3rd Aves.

Dunscombe Place was the former name of East 50th St. between 1st Ave. and Beekman Place.

Dunham Place was the former name of an Alley running south from 142 West 33rd St., now closed.

Dwar’s Street was the former name of Exchange Place between Broadway and Broad St.

Dyes Street. Dey Street was so called in 1767.

Eagle Street was the former name of Hester St.; it was laid out about 1750; known in 1755 as Hester St.; in 1766 as Eagle St., and since 1807 as Eagle St.

East Bank Street was an old road in Greenwich Village; it ran from 7th and Greenwich Ave. northeasterly to the Union Road in the block now bounded by 6th and 7th Aves., 13th and 14th Sts.

East Court was in West 22nd St. near 6th Ave.; now closed.

East George Street was the former name of Market St.

Eastern Post Road started at the present Broadway and 23rd St. and ran northeasterly across Madison Square to about 30th St. just west of Lexington Ave.; it then ran northerly, parallel to Lexington Ave. to 36th St., there veering easterly, crossing 3rd Ave. at 45th St. and then running northerly, midway between 2nd and 3rd Ave. to 50th St., where it turned northeasterly. Crossing 2nd Ave. at 52nd St., from there it ran northerly, midway between 1st and 2nd Aves. At 57th St. it turned slightly westerly, crossing 2nd Ave. at 62nd St., 3rd Ave. at 72nd, and Lexington Ave. at 76th St. It then ran northerly and northeasterly, recrossing Lexington Ave. at 77th St., then northeasterly, northerly and northwesterly, crossing 5th Ave. at 90th St., then northerly through Central Park, recrossing 5th Ave. at 109th St., Central Park, recrossing 5th Ave. at 109th St., 4th Ave. at 115th St., then northeasterly between 3rd and 4th Ave. to the Harlem River at 130th St. and 3rd Ave. This road was also called the Boston Post Road. It was closed in 1839.

East Place formerly ran in the rear of Nos. 184-186 East 3rd St., between Avenue B and C.

East Road was the former name of 4th Ave. between 37th and 90th Sts.

East Street was the former name of Mangin St.

East Tompkins Place was the former name of East 11th St. between Ave. A and B.

Ratzer Map, 1769

Eden Street was the former name of Morton St. between Bedford and Bleecker Sts. It was also called Arden St.

Eden’s Alley; see Ryder’s Alley.

Edgar Street was the former name of Morris St.

Edgars Alley was the former name of Exchange Alley.

Eighth Street was the former name of Hancock St.

Elbow Street was the former name of Cliff St.

Eliza Street was the former name of Waverly Place.

Eliza Street was a country road on the Kips Bay Farm. It started in the block bounded by 2nd and 3rd Aves., 28th and 29th Sts., and ran northeasterly, crossing 2nd Ave. at 35th St. and ended at 39th St., between 1st and 2nd Aves. It ran at right angle to two other old roads; Kips Bay St. and Maria St.

Ellet’s or Elliotts Alley was the name by which Mill Lane was known in about 1664. Elm Street was the former name of Lafayette St. between Worth and Spring Sts.

Erie Place was the former name of Duane St. between Washington and West Sts.

Exchange Court was in the rear of No. 74 Exchange Place.

Exchange Street was the former name of Beaver St. between William and Pearl Sts.

Exchange Street was the former name of Whitehall St.

Exchange Street was the former name of Marketfield St. In 1791 it was called Petticoat Lane.

Extra Place was an alley which ran north from 1st St. between the Bowery and 2nd Ave.

Factory Street was the former name of Waverly Place between Christopher and Bank Sts. It was also called Catherine St.

Fair Street was the former name of Fulton St. from Broadway to the Hudson River, east of Broadway it was called Partition St. It was laid out about 1720.

Farlow’s Court was formerly in the rear of Nos. 153, 155, 157, 159 and 161 Worth St.

Fayette Street was the former name of Oliver St. It was known as Oliver St. since 1825. From Park Row to Madison Sts.

Feitner’s Lane, see Verdant Lane.

Ferry Street was the former name of Bayard St.

Ferry Street was the former name of Peck Slip.

Ferry Street was the former name of Jackson St. between Division and Cherry Sts.; was known by this name in 1807; was also called Ferry Place.

Ferry Street was the former name of Scammel St.

Field Street, Fieldmarket Street were the former names of Marketfield St.

Fir Street ran from Grand St. to the East River between Scammel and Jackson Sts., now closed, it was also called Bar St.

Fifth Street was the former name of Orchard St.

Fifth Street was the former name of Thompson St.

Fifth Street was the former name of Washington St.

First Street was the former name of Christie St. from Division to Houston St. was known by this name in 1766.

First Street was the former name of Merces St.; was called Clermont St. in 1797; since 1807 known as Mercer St.

First Street was a former name of Greenwich St.

Fisher’s Court was in the rear of Nos. 22, 24 and 26 Oak Street, between Roosevelt and James Sts.

Fisher Street was the former name of Bayard St., from the Bowery to Division St., known by this name in 1755; since 1807 known as Bayard St.

Fitzroy Place was the former name of West 28th St. between 8th and 9th Aves.

Fitzroy Road, see Roy Road.

Flattenbarrack Street was one of the former names of Exchange Place, between Broadway and Broad St., it was known by this name in 1728.

Fourth Street was the former name of Allen St. between Division and Houston Sts.

Fourth Street was the former name of West Broadway between Canal and West 4th Streets.

Franklin Terrace was in the rear of No. 364 West 36th St.

French Church Street was the former name of Pine Street between Broadway and William St.

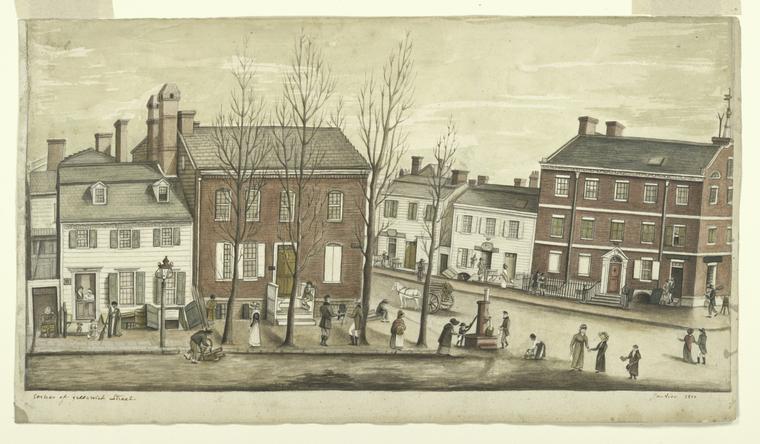

Greenwich Street 1810

Front Street was the former name of Greenwich St.

Fulton Street was a former name of Nassau St.

Garden Lane was the former name of Exchange Alley; was also known as Tin Pot Alley.

Garden Row was the former name of Nos. 140 to 158 West 11th St.

Garden Street was one of the former names of Exchange Place. This Street was laid out during the Dutch rule and was called by them Tuyn (Garden) Straet; in 1691 it was known as Church St., in 1728 as Garden St. and a part as Flattenbarrack; in 1797 it was all called Garden St. Garden Street was the former name of Cherry St. from Montgomery to Corlaers Sts.

Gardiner Street was the former name of Tompkins St.

Gen. Greene Street was the former name of Governeur St. George Street was the former name of Beekman St.

George Street was the former name of Bleecker St. between Hancock and Bank Sts.

George Street was the former name of Hudson St.

George Street was the former name of Market St. between Division and Cherry Sts. It was known by this name in 1791.

George Street was the former name of Park St.

George Street was the former name of Rose St.

George Street was the former name of Spruce St. It was laid out about 1725 as George St.; in 1817 it was known as Little George St.

Germain Street was the former name of Carmine St.

Gibb Alley ran from Madison St., between Oliver and James Sts., northwesterly about one-half a block.

Gilbert Street was the former name of Barrow St. between Bleecker and West 4th Sts.

Gilford Place was the former name of East 44th St. between 3rd and Lexington Ave.

Glassmakers Street, Glazier Street, was a former name of William St. between Pearl and Wall Sts.

Glover Place was one of the former names of Thompson St. between Spring and Prince Sts.

Golden Hill was the former name of John St. between William and Pearl Sts.

Grand Avenue was the former name of 125th St.

Great Dock Street was one of the former names of Pearl St. This street was known in 1657 as Pearl St.; in the same year was also known as Hoogh St. and the Waal; in 1691 as Great Dock and Great Queen Sts.; in 1728 as Queen St.; in 1728 as Queen St. in 1797 it was known as Pearl St. as far north as Park Row, the rest being called Magazine St. Since 1807 the entire street has been known as Pearl St.

Great George Street was the name Broadway, north of the City Hall Park, was known by in 1791.

Great Kiln Road see Southampton Road.

Green Alley or Lane was the former name of Liberty Place.

Greenwich Lane was the former name of Gansevoort and Greenwich Ave.

Greenwich Street, Washington St. was called by this name at one time.

Green Street was a former name of Liberty St.

Garry Place was the former name of West 35th St. between 7th and 8th Aves. Hamilton Place was the former name of West 5lst St.

Hamilton Place was the former name of West 51st St. between Broadway and 8th Ave.

Hammersly Street was the former name of West Houston Street between Macdougal St. and the Hudson River.

Hammond Street was the former name of West 11th St. between Greenwich Ave. and the Hudson River.

Hanson Place was the former name of 2nd Ave. between 124th and 125th Sts.

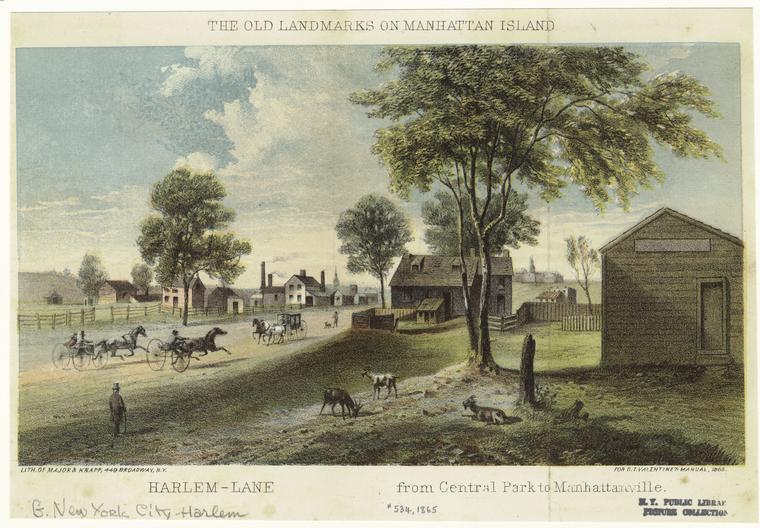

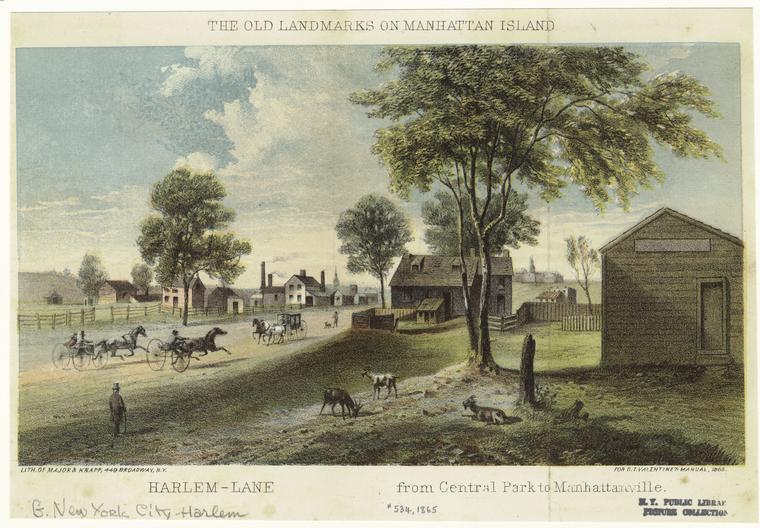

Harlem Lane, Sarony and Major, Valentine’s Manual, 1865

Harlem Lane. The present St. Nicholas Ave. from 110th to 123rd Sts. was called by this name; it was part of the Kingsbridge Road.

Harlem Road (The Old) was a country road leading to the Village of Harlem; it started at the junction of the Eastern Post Road in the Central Park about on a line of 108th St. and between 5th and Lenox Ave. running northeasterly; crossing Madison Ave. at between 113th and 114th Sts., Park Ave. between 115th and 116th Sts., Lexington Ave. between 117th and 118th Sts.; 2nd Ave. at 123rd St.; 1st Ave. at 125th St., and ending at the Harlem River at the foot of 126th St.

Harlem Road started at the Eastern Post Road, about the present 95th St. between Madison and 5th Ave.. and ran northeasterly, crossing Madison Ave. at 99th St.; Park Ave. at 108th St., Lexington Ave. at 116th St. and ending at the Harlem River at 129th St.

Harmon Street was the former name of East Broadway; it was originally a lane, known as Love Lane that led to the Rutgers Farm.

Harsen’s Lane was a country road which connected the Village of Harsenville (70th St. & Broadway) with the eastern part of the Island; it commenced at the Bloomingdale Road (the present Broadway) between 71st and 72nd Sts. and ran easterly about on line of the present 71st and ended at the Middle Road; the present 5th Ave. and 71st St.

Hazard Street was the former name of King St.

The Graft or Canal (Heer Graft ), 1659

Heer Graft (High Ditch) was the name given by the Dutch to the present Broad St. between Beaver and Pearl Sts. in 1657; it was one of the earliest streets laid out in the City, and received its name on account of the narrow Canal which ran through the center. This canal was filled in about 1676 and the street was called Broad St.; it was sometimes spelled Heeren Gracht.

Heere Straet, Heere Wegh, Heere Waage Wegh, were the Dutch names for the present Broadway between Bowling Green and the City Hall Park.

Hell Gate Ferry Road was a country road which ran from the East River at the foot of 90th St. southwesterly, joining the Eastern Post Road at Madison Ave. and 82nd St.

Hereweg. The Dutch name of the present Park Row from Broadway to Chambers St.

Herman Place was in the rear of Nos. 194, 1%, 198 Fourth St. between Avenues A and B.

Henry Street was the former name of Perry St.

Herring Street was the former name of Bleecker St. between Carmine and Banks Sts.; known by this name in 1817; name changed to Bleecker St. in 1829.

Herring Street was the former name of Mercer St.

Hester Court was formerly in the rear of No. 101 Hester St.

Hester Street was the former name of Howard St.

Hett Street, Hetty Street, were the former names of Charlton St.

Hevins Street was the former name of Broome St. between Broadway and Hudson Sts.; was also known as St. Hevins St.

High Street was the former name of Madison St. from Montgomery to Grand Sts.

High Street was the former name of Stone St.; known by this name in 1674.

Hohoken Street formerly ran from No. 474 Washington St. west to West St., now a part of Canal St.

Hoogh Straet (High Street) was the name of Stone St. east of Broad St. prior to 1664.

Hoppers Lane was a country road which ran from the Bloomingdale Road (the present Broadway), just south of 5lst St. westerly to the Hudson River at the foot of 53rd St.

Horse and Cart Lane was the name of part of William St.

Houston Street was the former name of Prince St. between Broadway and Hancock St.

Hubert Street was the former name of York St.

Hudson Place was the former name of West 24th St. between 8th and 9th Aves.

Hudson Street was the former name of West Houston Street between Broadway and Hancock St.

Hull Street was the former name of Bridge St. between Whitehall and Broad Sts.; known as Bridge St. in 1676; Hull St. in 1681; and Bridge St. since 1728.

Part two at https://gothamhistory.com/2015/06/09/street-names-changed-or-now-obsolete-part-2/.

![The Island of Manhados (with inset plan of) The Towne of New-York [The Nicolls Map or Survey], 1664-8.](https://gothamhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/plate-10-a-a-the-island-of-manhados-with-inset-plan-of-the-towne-of-new-york-the-nicolls-map-or-survey-1664-8.png?w=1000&h=347)